*As a child I was irascible—easily bored, prone to tantrums,

and always on edge. Luckily for my parents, they discovered a cure early on:

books. We’d make weekly trips to the library, where I’d fill up a tote bag with

as many books as it could hold. The bag was always so heavy that I’d have to

schlep it over my shoulder like a bindle, which was only cute because I was at

an age and size when carrying really heavy things was endearing rather than

pitiful.

*I’d check out more than thirty books at a time and finish

them all within a week. I’d often lock myself in my room, finishing seven

novels in a day. I was the kid who read under the table at family dinners and

was told my eyes would melt away for reading in the dark on in the car. I

discovered early on that books had a palliative effect on my otherwise choleric

temperament. Books became for me the tokens of comfort that stuffed animals were for many kids.

Libraries and bookstores were both places of discovery and havens of refuge.

*There’s a part of me that refuses to believe in the

possibility of obsolescence. Will books and libraries soon be, respectively,

the LPs and the record stores that we visit with a nostalgic glance? Are they

already mere emblems of authenticity, marks of a certain “type” of person whose

usage of books and libraries avows a certain devotion to higher principles? Are

libraries soon to be museums of objects rather than places where we go to

borrow books?

*Already, the function of libraries is changing—but then

again, perhaps they, like any institution, have always been dynamic. Many

people have written about the library as a “third place,” a term coined by RayOldenburg in his 1990 book, The Great Good Place. Simply put, a “third place”

is “a neutral social surrounding separate from home and work/school.”

Specifically, Kevin Harris, who writes about libraries as being third places,

writes, “all societies need places that allow informal interaction without

requiring it, places that are rich in the possibility of the safe, mundane

encounter…” Libraries can serve this function, but they should also be distinct

from other places of informal interaction, like cafes and parks, in their focus

and intent.

*If libraries are to survive, then they must be able to adapt

to their own changing functions, or people’s perception of their function—and

capitalize on their distinctiveness from other “third places.” Besides being a

meeting place, the library environment should foster, if not an appreciation

for books as objects of both beauty and experience, an appreciation of reading,

learning, and the pursuit of knowledge. They should expand both the breadth and

depth of intellectual exploration.

*One of my college professors, John Stilgoe—an eccentric man

whose curmudgeonly facade could never truly obscure his absolute brilliance and

kindness—said that the reason why he never sent research assistants to the

library and did all book-fetching himself is because of the serendipity that that happens when scanning bookshelves. In the process of seeking one book, you find another, whether tangential or relevant, that might be even better than the

one you were seeking in the first place. The same is true of a librarian’s

expertise: human knowledge, memory, and association create strands of

interpersonal discovery and sharing that we’ve tried to replicate in our digital

libraries, without complete success. Serendipity is diminished, if not lost in algorithmic

recommendations, and even the most personal of reviews online are less human than in a conversation, in a physical space.

*Can the design of a library, then, facilitate serendipity

and discovery while attracting the masses in an age where digital convenience

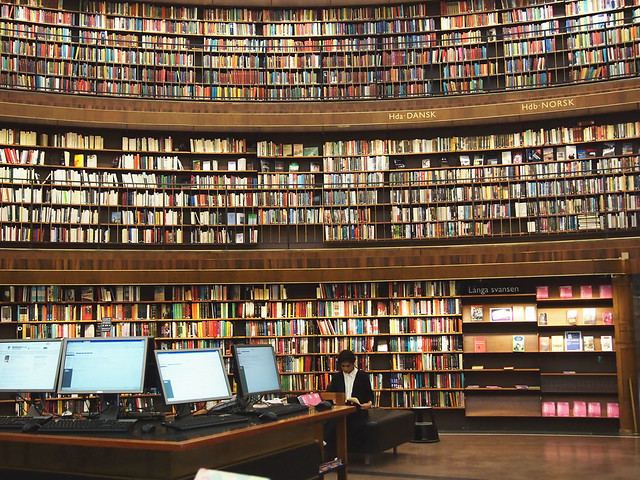

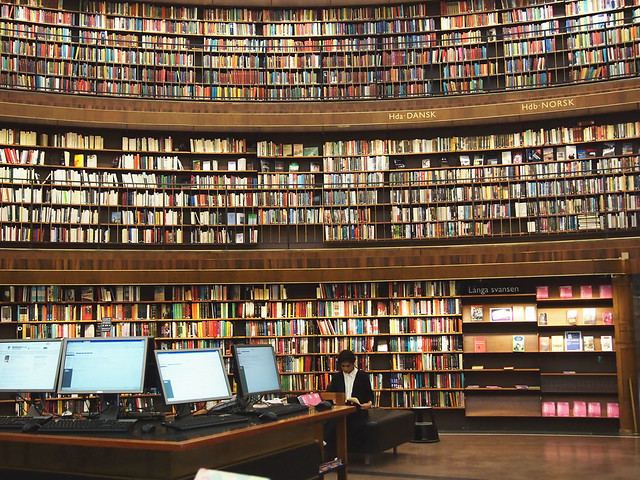

is highly prized and sought after? Last week I visited both the Stockholm Public Library and The Royal Library in Copenhagen, both of which are grand

pillars of design. To the credit of Swedish architect Gunnar Asplund, the

Stockholm Public Library’s most notable feature is its rotunda, which though

remarkable from the outside, is even more remarkable for the experience it

creates for the visitor upon entering the library: the feeling of being

enveloped in books, as in a forest, or a in a crowd. The modern design, which

is both functional and aesthetically pleasing, creates a sense of monumental

grandeur which does not preclude accessibility, which can often be the case in

spaces that feel larger-than-life. In fact, Asplund intentionally implemented

open shelving so that visitors could access books without the help of

librarians; this democratization and access is at the very heart of the

communal book-borrowing system.

*But in a day and age when borrowing books seems antiquated,

if not superfluous, the best libraries serve other functions. One of the

reasons I visited Lamont Library, when I was at Harvard, was to spend time in

the Woodberry Poetry Room, which housed rare archives and recordings. The room

also played host to readings and lectures, which were ends in and of

themselves, but also means for people to become acquainted with library’s

stock. The Seattle Central Library offers a list of the top ten things to do on

its “Plan a Visit” page, which include “Enjoy exciting public art,” “tap into

technology,” and “pick up a gift in the friendshop,” all of which are

extensions, not origins, of a library’s function. The word “library,” after

all, comes from the Old French word “librairie,” which means “collection of

books.” But even if these functions are necessary for libraries to survive,

they must also not eclipse the foundation of libraries: the books themselves.

*I say this because I love and romanticize books as objects.

(My one flash of kleptomania was during the summer before third grade, when I

stole Sweet Valley High books from the summer camp library; never has anything

else even tempted me like books have.) But despite that love, I admit that I am

also obsessed with my Kindle and visit libraries now for their architecture,

aesthetics, sometimes their food, and very often their bathroom, which is true

of my visits to the Stockholm, Copenhagen, and Berlin libraries.

*The Royal Library in Copenhagen seems at first glance to be

a library only in name. Situated on the waterfront, the black marble and glass facade

is a sleek backdrop for tanning in the sun, which is the preferred activity of

many who visit the library. Besides the sun-kissed visitors, the library also

houses a fancy, modern restaurant, a bustling cafe, and a concert hall, all of which could

stand alone, as if the library were a mall or arcade. None seems to need the word

“library” as a descriptor, as in a library cafe, or a library restaurant, or a library concert hall (in fact, those couplings all sound rather awkward), yet

all incentivize visits to the library—at the very least, a reason to

go inside the library after tanning outside. The structure, an eight-story atrium with wave-shaped walls and transversal corridors impresses more easily than its contents. Its modernity is a far cry from the beautiful University libraries I am acquainted with (Widener, most familiarly; Yale's libraries through Gilmore Girls episodes), but its structure's ability to captivate, the same.

*More than ever, we must recognize libraries as places of modernity, not antiquity, that we can utilize in non-traditional ways. It is only in doing so that we can perhaps keep their original purpose, as houses of books, intact. We rarely use the word "patron" anymore, but one of its root meanings, "protector," is an apt word for any book-lover's relationship to libraries, both public and private. In attendance and in finances, I want to patronize libraries. This is my love letter to libraries and the serendipitous discoveries we make inside: the books we find, the knowledge we devour, and the occasional human encounters. This is for all the times that books made me feel better, for all the times I escaped into libraries as a world unto themselves, for all that I've stolen and loved and read and learned. This is my plea to keep libraries alive.

*More than ever, we must recognize libraries as places of modernity, not antiquity, that we can utilize in non-traditional ways. It is only in doing so that we can perhaps keep their original purpose, as houses of books, intact. We rarely use the word "patron" anymore, but one of its root meanings, "protector," is an apt word for any book-lover's relationship to libraries, both public and private. In attendance and in finances, I want to patronize libraries. This is my love letter to libraries and the serendipitous discoveries we make inside: the books we find, the knowledge we devour, and the occasional human encounters. This is for all the times that books made me feel better, for all the times I escaped into libraries as a world unto themselves, for all that I've stolen and loved and read and learned. This is my plea to keep libraries alive.

Interesting... real libraries ARE books... it saddens me that many urban "libraries" have become internet coffee houses, sans the coffee. Most "reading" consists of staring at a monitor and watching cat videos on Youtube, or Facebook gawking, or playing video games online... so sad...

ReplyDelete